Project Waterworth

Meta’s Project Waterworth is a newly announced undersea cable initiative poised to reshape global internet connectivity. Touted as Meta’s most ambitious subsea project yet, Waterworth will span over 50,000 km and connect five continents, making it the longest high-capacity subsea cable system in the world (engineering.fb.com). This massive fiber-optic cable network is not just about length – it represents a strategic leap in technology and infrastructure aimed at supporting the next generation of digital demands, particularly the explosion of data-intensive AI applications. This report provides an in-depth analysis of Project Waterworth’s technological innovations and objectives, examines Meta’s long-term subsea infrastructure strategy, compares it with similar efforts by Google, Microsoft and others, and explores the economic, geopolitical, and security implications of these developments.

Technological Innovations of Project Waterworth

Project Waterworth represents a significant engineering advancement in submarine cable technology. At its core, the cable is designed for unprecedented scale and capacity, leveraging cutting-edge fiber-optic innovations:

-

Record-Setting Length and Capacity: Waterworth will exceed the Earth’s circumference in length (~50,000 km) and utilize the highest-capacity fiber technology available (engineering.fb.com). Meta has confirmed the system will deploy 24 fiber pairs, far above the typical 8 to 16 fiber pairs found in most new cables (subtelforum.com). This tripling of fiber count means substantially more bandwidth – enabling “industry-leading connectivity” across its route (engineering.fb.com) (subtelforum.com). By comparison, one of the highest-capacity existing cables, MAREA (completed in 2017 by Microsoft and Facebook), had 8 fiber pairs with a design capacity of 160 Tbps; Waterworth’s fiber count suggests it could far surpass that in throughput. The extra capacity is crucial for handling the massive data flows required by modern cloud services and AI workloads.

-

AI-Driven Design Philosophy: While the cable’s fibers carry data in the conventional sense, Project Waterworth is explicitly being built to support AI and emerging technologies on a global scale. Meta emphasizes that the project will provide the abundant, high-speed connectivity needed to “drive AI innovation around the world.” (engineering.fb.com) In essence, the cable’s huge bandwidth is “AI-driven” in that it’s motivated by exploding demand from AI applications – such as large-scale machine learning, which requires shuttling enormous datasets between data centers. Meta notes that AI is “transforming industries and societies,” making capacity, resilience, and global reach more important than ever for infrastructure (engineering.fb.com).

-

Advanced Fiber-Optic Technology: Project Waterworth will incorporate the latest fiber-optic innovations. The 24-pair design is an example of Space Division Multiplexing (SDM) – adding more fiber cores to increase total capacity efficiently. (For context, Amazon’s newest planned cable is expected to use a 12-pair SDM design (networkcomputing.com), while Google and NEC are even experimenting with multicore fiber (MCF) that bundles multiple optical cores inside a single fiber strand (subtelforum.com).) Meta is pushing the envelope by making 24 fiber pairs the new standard for long-haul cables. This high fiber count, paired with state-of-the-art signal boosting and wavelength technology, gives Waterworth an unmatched data-carrying potential. Meta’s recent engineering work on better in-line optical amplifiers (ILAs) is likely to play a role here – the company has been reimagining amplifier sites to improve performance and energy efficiency, which will be vital for a cable of this length (engineering.fb.com) (engineering.fb.com).)

-

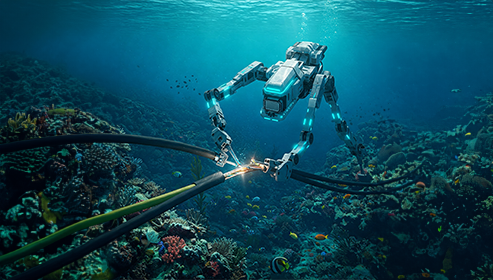

Resilient Routing and Installation Techniques: Beyond raw capacity, Waterworth introduces innovations in route engineering for resilience. Meta is deploying a “first-of-its-kind routing” that maximizes distance in deep ocean waters (down to 7,000 m depth) and minimizes exposure in shallow, hazard-prone areas (engineering.fb.com). Deep-sea routes reduce the risk of external damage since the cable lies far below ship traffic and fishing activity. In coastal shallows where cables typically face threats like ship anchors or trawling, Waterworth will use enhanced burial techniques – burying the cable deeper under the seafloor to protect it from disturbances (engineering.fb.com). These measures are meant to bolster reliability. Meta is clearly prioritizing a robust design after a recent wave of subsea cable disruptions globally. By routing around geopolitical hotspots and using careful burying methods, Waterworth’s engineers aim to minimize downtime and physical vulnerabilities.

In short, Project Waterworth is a showcase of next-generation subsea cable tech: an extremely long-haul, high-fiber-count system engineered for both extreme capacity and durability. It is “future-proofed” for the data deluge expected from AI and other digital growth areas. Meta describes it as opening three new oceanic corridors of connectivity to strengthen the world’s digital highways (engineering.fb.com), underscoring how this single project will create multiple new routes for internet traffic. If successful, Waterworth will set a new benchmark that other cable projects may follow – effectively building a dedicated global backbone for Meta’s data, with fiber-optic capabilities tuned to the demands of AI era connectivity.

Meta’s Long-Term Subsea Infrastructure Strategy and Global Connectivity Goals

Project Waterworth did not emerge in isolation – it is the culmination of Meta’s multi-year strategy of investing in internet infrastructure to extend its reach and control over global data delivery. Meta’s long-term vision for subsea cables aligns closely with its broader goals of connecting more people worldwide (thus expanding the user base of Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, etc.) and ensuring its platforms run on fast, reliable networks. Key aspects of this strategy include:

-

Building the Internet’s Backbone to Reach New Users: Meta (formerly Facebook) has for years framed connectivity as a central mission. The company has invested in dozens of cable projects through partnerships, explicitly “to build the infrastructure that carries internet traffic and help bring more people online faster.” (engineering.fb.com) For example, Meta is a lead partner in the 2Africa cable, a 45,000 km system encircling Africa (the prior record-holder for longest cable). 2Africa aims to dramatically improve internet access in Africa, the Middle East and Asia by tripling the total network capacity serving Africa (engineering.fb.com). Meta’s Connectivity VP cited Africa’s status as the least-connected continent (only ~25% of 1.3B people online) as motivation for that investment (engineering.fb.com). We see a consistent pattern: Meta identifies regions with growth potential (and currently limited bandwidth) and pours capital into backbone infrastructure to unlock new users and markets. Project Waterworth continues this approach on an even grander scale – it will connect regions like India, South Asia, Africa, and Latin America directly with the U.S. in a way that facilitates “digital inclusion” and economic development (subtelforum.com). In India, for instance, Meta expects Waterworth to “accelerate progress and support the country’s ambitious digital economy plans.” (subtelforum.com). Expanding connectivity isn’t just altruism; it directly feeds Meta’s business by enabling millions more people to use its social, communication, and metaverse services.

-

Ensuring Control and Capacity for Meta’s Own Services: As Meta’s applications and cloud services have grown, so has its share of global internet traffic – the company’s platforms now account for an estimated 10% of all fixed internet traffic and 22% of mobile traffic worldwide (subtelforum.com). By investing in subsea cables, Meta secures the capacity to carry this enormous traffic load on its own terms. Until now, Meta largely co-owned cables in consortia (it has partnered in over 16 existing submarine cables around the world (subtelforum.com) alongside telcos and tech peers). Waterworth marks a strategic shift: it will be Meta’s first fully owned, private subsea cable spanning the globe (subtelforum.com). This means Meta will be the sole operator and sole user of the system (subtelforum.com) – effectively a dedicated international backbone for Meta’s data. The long-term strategy here is self-reliance and performance optimization. Owning the cable end-to-end gives Meta greater control over routing, bandwidth allocation, and upgrade cycles, ensuring its services (from messaging to VR to AI cloud computing) are not bottlenecked by third-party infrastructure. According to insiders, this project (internally nicknamed “W” for its W-shaped route) is explicitly meant “to provide Meta with its own dedicated internet backbone to support the growth of its services globally, particularly given the rapid growth of AI.” (subtelforum.com). In essence, Meta is internalizing the internet’s backbone for its traffic – a trend also seen with other hyperscalers (Google, Microsoft, etc.) but Meta is now fully committing to it. This can reduce transit costs (fees paid to carriers) and improve reliability for Meta. It aligns with Meta’s broader goal of building out vertical infrastructure stacks (data centers, edge servers, fiber routes) that connect users to its platforms as directly as possible.

-

Strategic Partnerships and Economic Justification: Meta’s subsea projects often involve partnerships with regional operators and other tech firms, except for the new fully-private Waterworth. These partnerships help navigate regulatory requirements and share costs. For example, 2Africa involves multiple African and global telecom companies. By allying with local partners, Meta gains easier landing rights and political buy-in. Moreover, Meta frequently justifies cable investments by touting their economic benefits for connected regions. An internal study projected that Meta’s subsea cable investments would “contribute over half a trillion dollars to Asia-Pacific and European economies by 2025.” (tech.facebook.com) Such claims position Meta’s projects as public-good infrastructure, aligning with global development goals. Indeed, robust internet links can boost GDP by enabling e-commerce, remote work, and digital services. Project Waterworth is marketed in a similar vein: Meta says it will “enable greater economic cooperation, facilitate digital inclusion, and open opportunities for technological development” in the regions it touches (subtelforum.com). By aligning its projects with host countries’ goals (like India’s digital economy push), Meta secures goodwill and smoother approval for its expansive network.

-

Broad Connectivity Initiatives: Subsea cables are one pillar of Meta’s connectivity strategy, complementing other efforts. In the past, Facebook tried experimental projects like high-altitude drones (Aquila) and satellites to reach remote areas. Those proved less practical; subsea fiber, while expensive, delivers far more bandwidth and reliability. Meta also spearheads the Telecom Infra Project (TIP) and invests in terrestrial fiber, Wi-Fi hotspots (Express WiFi), and other telecom innovations. All these efforts align with a singular mission: make accessing the internet (and by extension, Meta’s services) as ubiquitous and affordable as possible worldwide. The long-term payoff for Meta is increased user growth and engagement on its platforms, which drives advertising and potential metaverse adoption. By literally building the highways of the internet, Meta is positioning itself not just as a content platform but as an infrastructure provider. Project Waterworth signals that Meta intends to remain at the forefront of global connectivity build-out for the foreseeable future, directly tying infrastructure prowess to its company vision. As Meta’s engineers put it, such investments “enable unmatched connectivity for our world’s increasing digital needs.” (subtelforum.com)

In summary, Meta’s strategy in subsea infrastructure is twofold: grow the pie of global internet connectivity (especially in underserved regions) to bring more people into the digital fold, and secure a private, high-performance network for Meta’s own traffic in the AI age. Project Waterworth perfectly embodies this, as it will both create new internet pathways linking multiple continents and serve as Meta’s independent “data highway” circling the globe.

Comparisons with Google, Microsoft, and Other Undersea Cable Initiatives

Meta is not alone in its undersea cable ambitions – in fact, the world’s largest technology companies have become the dominant drivers of new submarine cable deployments in the past decade. These firms, often called content providers or hyperscalers, have needs for bandwidth and global data transport that far exceed those of traditional telecom carriers. Let’s compare Meta’s Project Waterworth and strategy with similar projects undertaken by Google, Microsoft, and others:

-

Google: Among all tech companies, Google has been the most aggressive investor in subsea cables. It is currently “the world’s largest owner and investor in submarine cable networks,” according to industry research. (networkcomputing.com). Between 2016 and 2018 alone, Google poured $47 billion into expanding its global cloud infrastructure, including investments in at least 14 subsea cables (networkcomputing.com). Google has both partnered in consortia and built privately-owned cables to link its data centers across oceans. Notable Google cable projects include:

Google often names its cables after scientists and has made a point to become self-reliant in connectivity for its services (Search, YouTube, Google Cloud). It currently has investments in dozens of cables globally, some co-owned (e.g., Jupiter in the Pacific, Havfrue/AEC-1 in the North Atlantic) and many solely owned. Capacity and innovation-wise, Google has driven technologies like space-division multiplexing and multicore fiber. In the Asia-Pacific region, Google partnered with NEC to pioneer a multicore fiber (MCF) cable linking the U.S., Taiwan, and Philippines (the *“TPU” cable) – essentially doubling fiber capacity by using fibers with multiple cores to carry more light (subtelforum.com). This is the first such deployment of MCF in the world (subtelforum.com), highlighting how Google pushes the boundaries of fiber-optics. Compared to Meta’s Waterworth, Google’s approach is slightly different: rather than one giant loop, Google builds multiple specialized cables on key routes. However, the end result is similar – Google has a globe-spanning network. In fact, Google’s infrastructure is so extensive that by 2022 content providers (led by Google) were carrying 66% of all international internet traffic – up from less than 10% in 2012 (blog.telegeography.com). Google’s investments have essentially “outpaced all others” in undersea capacity growth (blog.telegeography.com). Meta, with Waterworth, is now trying to catch up and ensure it has a comparable private backbone.- Grace Hopper, a transatlantic cable connecting the U.S. to the UK and Spain (announced 2020, went live 2022), aimed at improving Google Cloud and Google services in Europe

- (networkcomputing.com).

- Dunant, a private Google cable between the U.S. and France (went live 2021) which set records with 250 Tbps capacity on 12 fiber pairs.

- Equiano, connecting Portugal down the west coast of Africa to South Africa (completed in 2022), bringing high-speed internet to multiple African countries.

- Curie, linking California to Chile (completed 2019), giving Google a direct South American link.

- Nuvem, a new transatlantic system connecting South Carolina (US) to Portugal and Bermuda, due to be operational by 2026

- (networkcomputing.com).

- Australia Connect, announced in 2024, extending Google’s network to Australia and the Pacific islands

- (networkcomputing.com).

-

Microsoft: Microsoft has also invested heavily in subsea cables to connect its global Azure cloud data centers and services. Its strategy has often been to partner in consortium cables or buy large capacity stakes, rather than solely build for itself. One of Microsoft’s landmark collaborations was with Facebook (Meta) on the MAREA cable across the Atlantic. MAREA, completed in 2017, connects Virginia Beach (US) to Bilbao, Spain, and was “the most technologically advanced subsea cable to cross the Atlantic” at launch, with 8 fiber pairs and 160 Tbps design capacity (fierce-network.com). Microsoft and Facebook jointly funded MAREA to support their cloud and social platforms, showing early on the value of content providers teaming up to improve infrastructure. Microsoft is also a part-owner of cables like Amitié (a transatlantic system connecting the US, UK, and France), New Cross Pacific (NCP) connecting the US to Asia, and SEA-ME-WE 6 from Southeast Asia to Europe (blog.telegeography.com). In the Pacific, Microsoft joined others on cables to Australia and Asia to ensure connectivity for Azure and Office 365 services. An official Microsoft blog noted the company “is investing in a cable with each [partner] to connect Microsoft’s datacenter infrastructure from North America to Ireland and on to the UK.” (azure.microsoft.com) (This references the Amitié cable system.) Compared to Google and Meta, Microsoft has fewer wholly-private cables, but it secures fiber pairs on many routes for its exclusive use. The end result is a robust mesh connecting Microsoft’s cloud regions. With Meta’s Waterworth going fully private, we may see Microsoft consider more private builds too in the future to keep up, especially as Azure’s bandwidth needs grow with AI and cloud services.

-

Amazon: Amazon, another hyperscaler via its AWS cloud, was initially slower to invest in subsea cables but has ramped up recently. By 2025, Amazon is involved in new cable projects to bolster its network connectivity for AWS data centers and retail operations. For instance, Amazon has filed for a license to land a US–Ireland cable to connect its data centers in Ireland directly to North America (networkcomputing.com). That cable is expected to be a 12-fiber-pair SDM system (for high capacity) (networkcomputing.com). Amazon also reportedly joined the Jupiter cable consortium in the Pacific and is looking at routes into Africa and Asia as its cloud expands. Like Meta, Amazon recognizes that even a few seconds of connectivity loss can cost millions in e-commerce sales (networkcomputing.com), so they are investing for redundancy and performance. By joining the subsea cable club, Amazon (along with Google, Meta, Microsoft) underlines that ownership of infrastructure = competitive advantage in the cloud and internet economy. It’s worth noting that as of 2020, content providers collectively account for over 65% of new submarine cable capacity (blog.telegeography.com) – a stark shift from a decade ago when telecom carriers dominated. Now, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon are effectively becoming the new backbone carriers of the global internet.

-

Other Tech Firms and Initiatives: Beyond the “Big Four,” other players also have stakes:

- Telecom and Consortium Cables: Traditional telecom companies still build many cables, often in consortia that include tech firms. For example, Telecom Italia’s Sparkle, Orange, Verizon, NTT, and others frequently partner with hyperscalers. The trend is that hyperscalers often foot a large portion of the bill in exchange for dedicated fiber pairs on these new cables.

- Chinese Tech Companies: China’s content and cloud companies (like Tencent, Alibaba) have started investing in regional cables, though geopolitical tensions limit their global reach. There are also China-led cables, such as the PEACE cable (connecting Asia, Africa, Europe) and proposals for Arctic routes, which can be seen as parallel infrastructure to Western-aligned projects. For instance, a proposed U.S.-Asia cable with Chinese partners was scrapped due to U.S. security concerns

(businessinsider.com).

In comparison to its peers, Meta’s Project Waterworth is most analogous to Google’s strategy: it is a bold attempt to build a comprehensive, private global network. The difference is Meta is doing it in one sweeping project (with a “World Loop” cable), whereas Google achieved similar coverage with multiple cables over time. Microsoft and Amazon are a bit more cautious or collaborative, but even they are trending toward more direct ownership as data demands grow. All major tech firms recognize that undersea cables are strategic assets – controlling them means controlling the flow of data across the planet. As a result, we’re witnessing an unprecedented boom in undersea cable construction funded by these companies. Industry analysts note “there are a lot of cables entering service in the next three years” due to content provider demand, on routes like Trans-Pacific and Intra-Asia which are seeing record investments (blog.telegeography.com) (blog.telegeography.com). Project Waterworth slots into this context as one of the marquee efforts of the 2020s, alongside Google’s newest transoceanic cables and consortium builds involving multiple tech giants.

Economic and Geopolitical Stakes

The rise of mega-projects like Project Waterworth carries significant economic and geopolitical implications. Undersea cables are often called the “backbone” or “arteries” of the global internet, and control over these arteries is increasingly strategic. Here’s a closer look at the high stakes:

-

Critical Infrastructure for the Global Economy: Submarine fiber-optic cables carry an estimated 95% of all intercontinental internet traffic (networkcomputing.com). Everything from YouTube videos to financial trades to personal messages flows through these slender undersea fibers. They also facilitate around $10 trillion in financial transactions every day (networkcomputing.com). In short, modern globalization – communications, commerce, finance – depends utterly on undersea cables. A single cable outage can disrupt internet connectivity for millions or halt crucial data flows between continents. By investing $10+ billion in Waterworth, Meta is strengthening this critical infrastructure, but also inserting itself as a major controller of it. The economic stakes are enormous: whichever entities own the cables can influence the cost and quality of global bandwidth. For developing regions, a new cable can mean a huge boost in GDP growth (through improved digital access), while for Meta, owning cables reduces its reliance on telecom middlemen and can save on bandwidth costs long-term. Meta cites benefits like improved digital economies in India, Africa, etc., but also clearly benefits by ensuring its own products perform well in those markets. There is a delicate balance here – these private investments yield public good (connectivity), yet also concentrate infrastructure power in a few corporations.

-

Geopolitical Influence and Internet Control: Undersea cables have geopolitical importance akin to oil pipelines or shipping lanes. They determine who connects with whom, and through which pathways. By building new routes (like Waterworth’s planned corridors), Meta is re-drawing the map of internet connectivity. Notably, Waterworth’s route is being designed to avoid certain high-risk or politically sensitive regions – it “is designed to avoid high-risk geopolitical regions like the Red Sea, South China Sea, and the Strait of Malacca.” (subtelforum.com). These are chokepoints where cables have historically been vulnerable (e.g., Egypt’s Red Sea route where multiple cables cluster and have faced outages, or the South China Sea where territorial disputes raise security fears). By bypassing these areas, Meta reduces the chance that any single country or conflict could cut off its global network. However, this also has geopolitical signaling: it avoids routes dominated by Chinese influence (South China Sea) and unstable zones (the Middle East). In effect, Meta’s cable will skirt around China’s periphery and connect the U.S. to Asia/Africa via alternate paths (e.g., going around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean). This could shift internet traffic patterns away from traditional hubs (like avoiding the Suez/Red Sea route that connects Europe-Asia). Countries that used to sit on major cable routes might lose some strategic leverage, while new regions (like South Africa or Australia, which Waterworth will touch) gain greater importance as junctions. On the flip side, China and other nations are investing in their own cables to ensure they aren’t dependent on U.S. tech giants’ infrastructure – we may see a bifurcation where Western-aligned networks and Chinese-aligned networks operate in parallel, each avoiding the other’s territory.

-

National Security and Sovereignty Concerns: Control of undersea cables is now a national security issue for many governments. A clear example is the U.S. government’s 2020 move to block a Facebook/Google undersea cable connection into Hong Kong. The Pacific Light Cable Network (PLCN) was originally intended to link Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Philippines. However, U.S. authorities intervened and denied the Hong Kong landing on national security grounds, citing fears that the cable could be tapped by Beijing after Hong Kong’s autonomy weakened (businessinsider.com). The project had to be reconfigured to exclude the Hong Kong segment entirely (businessinsider.com). (businessinsider.com). This incident underscores how data sovereignty and security can override corporate plans. Countries worry that a cable landing in rival territory could expose communications to espionage or control. Similarly, some European regulators have expressed concerns about critical internet infrastructure being owned by foreign corporations. While most countries welcome new cables for the economic benefits, they often require that a local entity participate in the landing station for oversight. Meta’s Waterworth will have to navigate these regulatory approvals in each landing nation (U.S., Brazil, South Africa, India, Australia, etc.), potentially having to partner with local telecoms or create subsidiaries to satisfy legal requirements. International law (such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea) guarantees the freedom to lay cables in international waters, but the sensitive points are where cables come ashore, which is under national jurisdiction. We can expect intense scrutiny from governments to ensure their data sovereignty isn’t compromised by Waterworth. For instance, India might insist on data handling guarantees, or the U.S. may require security reviews (via Team Telecom) for any foreign involvement in segments of the cable.

-

Shift in Control from States to Private Companies: Historically, international telecommunications were dominated by state-owned or state-regulated carriers. Now, a handful of private tech giants are taking the helm. This raises questions about who “controls” the global internet infrastructure. If Meta owns a cable outright, it controls how that capacity is used – in this case, Meta says Waterworth is primarily for its own use (not a commercial system for others). That means a significant portion of the world’s intercontinental connectivity becomes essentially a private highway for one company’s data. Google similarly operates some private cables just for YouTube/Google traffic. For the public and businesses, this trend could be a double-edged sword: on one hand, it can relieve congestion on public networks (since Meta and others carry their internal traffic on their own cables, leaving more room on other cables for general use). On the other, it concentrates network resources – a failure or policy change by one of these companies could have outsized effects. Also, smaller countries or ISPs might have fewer alternative routes if big tech cables don’t offer capacity to the market. International regulators and organizations are starting to pay attention to this dynamic. There are discussions in forums like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and others about ensuring open access and competition on vital routes. Thus far, content providers have largely been welcomed as they accelerate cable deployment worldwide. But as their dominance grows, we may see calls for regulatory measures to prevent any single entity from “chokepoint” control of global bandwidth.

-

Economic Boost and Dependency: On the positive side, new cables like Waterworth can hugely benefit economies by lowering internet costs and improving speeds. Meta’s own analysis suggests massive GDP impacts from improved connectivity. African and South Asian countries connected to 2Africa/Waterworth could see new tech industries emerge, bridging the digital divide. However, there is also a potential dependency trap – if a country’s connectivity comes primarily through a cable owned by Meta (or Google, etc.), they become reliant on that company’s continued operation and favorable terms. This could give companies subtle leverage: e.g., in negotiations over data regulation or taxes, a company might be in a stronger position if it essentially owns the pipe carrying a nation’s traffic (though any overt abuse of such leverage would trigger backlash and regulators could always land alternative cables with competitors given time).

In essence, the economic and geopolitical stakes of Project Waterworth are immense. It reinforces the global internet’s physical underpinnings, bringing more capacity and redundancy (good for everyone), but it also exemplifies the shift of internet power towards a few private entities. The project’s conscious routing decisions reflect geostrategic thinking to avoid contested areas, likely a response to growing concerns of sabotage and surveillance. As more critical infrastructure goes under private control, expect continued debate over how to balance the efficiency of private investment with the need for national security and equitable access.

Key Risks and Challenges

Building and operating a subsea cable network of this magnitude comes with a host of risks and challenges. Project Waterworth, and similar undertakings, must contend with technical, security, and regulatory hurdles. Below are the key issues and how they might impact Meta’s project:

-

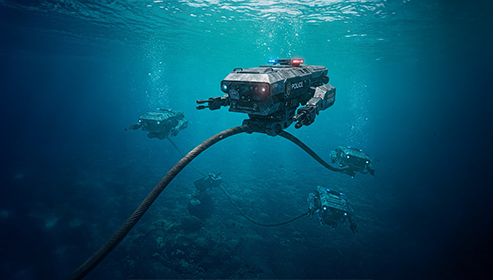

Physical Vulnerabilities and Sabotage: Undersea cables, despite being coated in steel armor and buried undersea, are physically fragile in the face of intentional or accidental damage. More than 100 cable faults occur each year on average (capacitymedia.com), mostly due to fishing trawlers, ship anchors dragging, or natural disasters (earthquakes, undersea landslides). In recent years, sabotage and deliberate attacks have become a real worry. For example, in 2022–2023, a series of mysterious cuts hit cables in the Baltic Sea and North Sea, coinciding with geopolitical tensions; European officials have grown nervous about the possibility of hostile actors (like Russian submarines) targeting critical cables (capacitymedia.com). In another incident, multiple cables in the Red Sea were cut in 2022, disrupting East African connectivity, with suspicion falling on potential sabotage amid conflict in Yemen. Meta is addressing some of this risk by smart routing (deep sea paths and avoiding certain chokepoints) (engineering.fb.com). (subtelforum.com), but the risk is never zero. Repairing a cut in a remote ocean can take days or weeks, during which connectivity is rerouted through other paths at reduced capacity. If Waterworth is truly for Meta’s exclusive use, a major cut could cripple Meta’s services in affected regions until repaired – a risk Meta will try to mitigate by also retaining capacity on other cables and building redundant loops. To guard against sabotage, companies are now working with governments to increase surveillance of cable routes. Notably, new AI-powered monitoring software has emerged that tracks ship movements near subsea cables and alerts operators and coast guards to suspicious behavior (for instance, a ship loitering where a cable lies) (capacitymedia.com). (capacitymedia.com). Windward, a maritime intelligence firm, launched such a system in 2025 to help protect against the staggering implications of undersea infrastructure sabotage (capacitymedia.com). Meta may leverage similar tools to safeguard Waterworth. Additionally, because Waterworth is largely in deep water, it’s less exposed – but when it comes ashore at landing sites, those segments will need heavy protection and quick repair capabilities. Physical security of cable stations is also critical (to prevent tampering or terrorism). In short, cable cuts – whether accidental or deliberate – are a top operational risk that Meta will face continuously once Waterworth is deployed.

-

Cybersecurity and Data Privacy: The cables themselves carry pulses of light that represent data – and while tapping a fiber-optic cable is not trivial, it’s not impossible. Intelligence agencies have in the past managed to siphon data from undersea cables (historically via special submersibles or at landing stations). Cybersecurity vulnerabilities for subsea cables typically center on the landing infrastructure: the network equipment that interfaces the optical fiber with the terrestrial internet can be hacked if not properly secured. There’s also risk in the supply chain – for instance, if a hostile entity somehow implanted malware in the cable repeaters or network management system. Meta will need to ensure robust encryption for any sensitive data traversing Waterworth, so that even if someone tapped the fiber, the data would be unintelligible. (Major tech firms already encrypt inter-datacenter links after past revelations of government tapping.) Another cybersecurity aspect is the control systems for the cable. Modern cables are actively managed by software that adjusts power levels of repeaters and monitors faults. A cyber attack on these management systems could theoretically disrupt cable operation. This risk is mitigated by keeping control systems isolated and redundant. Meta’s experience in running global data centers likely gives it expertise to harden Waterworth’s network against hacking. Data privacy and sovereignty concerns also come into play: governments may worry that data flowing on Meta’s privately-owned cable could be subject to interception by Meta itself or U.S. authorities. While companies generally don’t peek at the bits they carry (beyond what’s needed for routing), the perception of potential privacy issues could invite regulatory oversight. Meta will have to maintain strong transparency and compliance with local data laws for any data transiting through Waterworth’s links. For example, the EU’s GDPR and other regulations might require Meta to ensure European user data carried to India or the U.S. has adequate protections.

-

Regulatory and Legal Hurdles: Laying a cable across multiple jurisdictions requires navigating a labyrinth of permits, licenses, and regulatory approvals. Each country where Waterworth lands will likely require a cable landing license or franchise. In the U.S., for instance, the FCC in coordination with national security agencies (Team Telecom) must approve any cable landing – a process that can be stringent if foreign ownership is involved. Meta being a U.S. company should ease U.S. approvals, but other nations will conduct their own reviews. There could be national security reviews especially in countries like India or Brazil, to ensure that the cable landing does not compromise their interests. Additionally, international agreements like treaties on telecommunications and the law of the sea provide frameworks, but enforcement is up to states. Potential regulatory challenges include:

- Ownership restrictions: Some countries mandate that a domestic telecom operator co-own or at least operate the cable landing station. If Meta intended to be sole owner, it might have to create local subsidiaries or partner with an ISP in certain countries to satisfy these rules.

- Antitrust and Competition: Regulators might look at whether Meta’s exclusive use of a cable could hurt competition. For example, if Waterworth lands in Country X and Meta decides not to provide any excess capacity to others, will that put local carriers at a disadvantage or create bandwidth scarcity for others? Typically, one private cable doesn’t monopolize a route because multiple cables often exist. But if Waterworth becomes a major route on, say, the India–US corridor and it’s closed, it could raise concerns. Regulators might encourage Meta to lease spare capacity to third parties for resilience of the broader internet.

- Environmental and Permitting: The cable will need environmental clearances, especially for where it comes ashore and if any protected marine areas are along the route. While undersea cables have a relatively low environmental footprint (mostly on the seabed), any coastal work can trigger environmental assessments.

- Delays in Deployment: As noted earlier, the specialized ships that install cables are often booked out years in advance (subtelforum.com). Meta faces a logistical challenge coordinating the lay of 50,000 km of cable possibly in segments. Any regulatory delay in one country could upset the schedule since the cable likely has to be laid sequentially. For instance, if one landing country hasn’t approved by the time the cable ship is scheduled to be in that region, Meta might have to pause and return later, adding cost and complexity. Project Waterworth is a multi-year endeavor (engineering.fb.com) – managing the timeline and regulatory dependencies will be a major project management challenge.

-

Data Sovereignty and Political Pushback: As mentioned, countries might not be entirely comfortable with a foreign corporate entity controlling a key piece of their connectivity. This falls under data sovereignty debates. Some nations (India among them) have discussed requiring certain data (especially government or sensitive data) to route domestically or via neutral networks. If a substantial portion of a country’s international traffic goes over Waterworth, that country might fear losing some oversight. They might demand traffic monitoring capabilities or guarantees from Meta. In extreme cases, a government could delay or block a landing license if they feel their strategic interests aren’t met. For example, had Meta tried to land Waterworth in a country under U.S. sanctions or in China, it likely would face blocks – but Meta has smartly chosen politically friendly endpoints. Nonetheless, even allies can have concerns (Europe has been cautious about U.S. digital dominance). There’s also the optics issue: if Meta’s cable is seen as too powerful, governments could down the line push for policies to “open” such private cables for public use in emergencies, etc. All this means Meta will engage in a lot of diplomacy to reassure stakeholders that Waterworth is a boon, not a threat.

-

Maintenance and Operational Costs: Once built, a cable like Waterworth will incur ongoing costs for maintenance, repairs, and upgrades. Meta will have to either maintain an internal team or contract operators to handle this (many cable consortia hire specialized maintenance agreements). The cost of repairing a single break can be hundreds of thousands of dollars. If Waterworth has multiple segments, maintaining cable stations and power feeding equipment in each landing country is also non-trivial. Any prolonged outage on one segment might force Meta to route traffic on longer paths (latency could increase for users as a result). Ensuring resiliency means possibly interconnecting Waterworth with other cables at strategic hubs, which Meta likely will do. For example, in Brazil or Australia, Meta could interlink Waterworth with existing regional cables to provide alternate routing. This complexity of integration with the global network is an operational challenge but necessary for robustness.

In summary, while Project Waterworth is visionary, Meta will have to overcome a gauntlet of challenges: protecting the cable from cuts and attacks, securing it against cyber threats, placating regulators and governments on various fronts, and managing the sheer complexity of deployment and maintenance. The company’s experience with prior cable projects and its deep pockets give it an advantage, but the ocean is an unpredictable place – both physically and politically. How Meta navigates these risks will determine if Waterworth truly delivers on its promise of a more resilient, AI-ready global infrastructure.

Future Trends and the Role of AI in Subsea Cable Infrastructure

Project Waterworth is part of a broader wave of innovation in subsea cables, and it likely foreshadows key future trends in how these critical systems are built and operated. Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI) is set to play an increasingly important role in shaping and managing the next generation of digital infrastructure. Here’s a look at what the future might hold:

-

Continued Growth in Cable Capacity: The demand for international bandwidth shows no signs of slowing. Industry data indicates transoceanic bandwidth usage has been growing ~30–40% year-over-year in major routes (blog.telegeography.com), driven largely by cloud computing and video. We can expect future cables to push even higher fiber counts and novel fiber technologies. Today’s cutting-edge is 24 fiber pairs (Waterworth) or multicore fibers (Google’s TPU cable) – tomorrow’s cables might combine both, e.g., using multicore fibers with many fiber pairs. Researchers are already testing fibers with 4, 7, or even 19 cores inside a single strand, which could multiply capacity without needing thicker cables. We may see cables that effectively have 40-50 “fiber pair equivalents” in coming years. This will be crucial as applications like 8K video streaming, immersive VR/metaverse experiences, and globally distributed AI training generate unprecedented data flows.

-

New Routes and Redundant Meshes: The global cable network is becoming more meshed, with alternative routes reducing single points of failure. We will likely see more trans-Arctic cables (companies have explored Arctic routes to shorten latency between Asia and Europe, though geopolitical issues with Russia have stalled some projects). There’s also interest in a Latin America to Asia cable (bypassing North America) to create direct links between those regions. As climate change opens polar sea routes, cables through the Arctic Ocean (connecting Europe-Asia north of Russia) could re-emerge as a viable project, potentially backed by governments for strategic diversity. In the next decade, the cable map will become denser, with multiple cables connecting the same regions for backup. For example, by the time Waterworth is live, there might be other new cables from the U.S. to India or South Africa by different consortia, ensuring that even if one cable has issues, traffic can failover. The concept of a “global fiber ring” connecting all continents will move closer to reality – Waterworth is one such ring; others may intersect it at hubs. This redundancy is important given the rising threat environment for cables.

-

AI for Network Management and Maintenance: One of the most exciting trends is applying artificial intelligence to manage and protect cable infrastructure. As highlighted by industry experts, AI can be used “for Infrastructure” i.e., to optimize how networks operate (subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com). We can expect AI systems to continuously monitor the performance of cables like Waterworth, analyzing sensor data, power levels, and traffic patterns to detect anomalies. Predictive maintenance is a key benefit: AI algorithms can detect subtle signs of fiber stress or repeater degradation and alert engineers before a failure occurs (subtelforum.com). For instance, if the optical signal loss in a segment starts increasing beyond a threshold, an AI could flag that as a potential fiber pinch or marine event and dispatch a repair crew preemptively. AI can also optimize traffic routing in real time, rerouting data along different paths if one path shows congestion or instability (subtelforum.com). This kind of adaptive network can improve latency and throughput for users without human intervention. Meta, Google, and others are certainly investing in such intelligent network control – essentially bringing principles of self-driving cars to the “self-driving network.” Moreover, AI-driven security will be crucial. As mentioned, AI can correlate shipping data, weather, and historical patterns to predict high-risk scenarios for cable cuts and alert authorities (capacitymedia.com). It can also help in distinguishing between benign faults and malicious interference by analyzing data from multiple cables and sensors.

-

Infrastructure for AI (Growing Data Needs): Conversely, AI itself is influencing what infrastructure is needed (the “Infrastructure for AI” side of the coin) (subtelforum.com). Training advanced AI models (like large language models or deep neural nets) requires moving massive datasets across continents – often researchers will distribute training across data centers in different regions for speed or regulatory reasons (subtelforum.com). This means future cables must not only have high capacity but also low latency and ultra-high reliability to sync AI workloads. We may see specialized “AI cables” that connect major AI compute hubs. For example, if one city becomes an AI supercomputing center and another is an AI data repository, there might be dedicated links optimized between them. While any fiber can carry any data, providers might market certain routes as particularly low-latency (by using shortest path routing and new fiber tech) for AI and high-frequency trading needs. The growth of edge computing and 5G will also place new demands – with more data collected at the edges needing backhaul via subsea cables to central clouds.

-

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability: Future cables will also focus on power efficiency. Repeaters in a long cable like Waterworth require a lot of electrical power feed. Meta and others are working on reducing power consumption per bit (one reason for SDM is to operate many fiber pairs at lower power each, which is more efficient than pushing a few fibers to absolute max). ILA (In-line amplifier) innovation like Meta’s ILA Evo project aims to deploy amplifier sites on land more quickly and efficiently (engineering.fb.com). (engineering.fb.com) – similar principles might apply undersea, where repeaters could become more efficient or even leverage advancements like Raman amplification to stretch distances with less electrical input. Some researchers are exploring if renewable energy or kinetic energy from currents could ever power ocean repeaters, though that’s not yet practical. Still, as sustainability becomes important, hyperscalers may ensure their cable projects use eco-friendly processes and that they optimize power usage, which indirectly lowers the carbon footprint of data transport.

-

Regulatory Evolution: With private cables becoming so critical, we might see new international frameworks or cooperative measures to protect them. NATO and allied navies are already increasing patrols around cable zones in response to sabotage fears. There could be treaties or agreements for mutual assistance in cable repairs, or “no tampering” pledges (though enforcement is tricky). If the geopolitical bifurcation intensifies, we may even end up with parallel internets with limited interconnection – however, that scenario is extreme and costly, so most stakeholders prefer a globally interoperable network with multiple redundancies. Regulators might also push for open cable systems – an emerging idea where a cable’s capacity is not locked to one vendor’s equipment, allowing easier upgrades and multi-tenant usage. Open cable architectures combined with spectrum-sharing tech (where each company can use certain spectrum on the fiber rather than whole fiber pairs) could allow new players to tap into existing cables without laying new fiber, increasing efficiency. AI could facilitate such dynamic sharing by allocating optical spectrum on the fly to those who need it.

-

Integration with Terrestrial and Satellite Networks: Future digital infrastructure will see subsea cables integrated in a holistic network fabric along with terrestrial fiber, wireless, and satellite links. While low-earth-orbit satellite constellations (e.g., Starlink) are not a direct competitor to subsea cables for bulk data (satellites have far less capacity), they can complement in providing backup paths or serving remote areas. There’s research into using satellites to beam connectivity between cable endpoints as a failover in case a cable is cut. AI could manage such complex handoffs between undersea fiber and satellites during outages. Also, terrestrial fiber corridors are expanding (like new cross-border links in Asia, Europe, Africa) – combined with subsea cables, they create a multi-path global network. The ultimate goal is a network that is highly resilient and orchestrated by intelligent software, where the physical medium (sea, land, sky) is abstracted away. Users simply experience a connected world, while behind the scenes AI systems route their data via the best path available, be it a Meta cable under the Atlantic or a SpaceX satellite over the Pacific, all seamlessly.

Project Waterworth is both a product and enabler of future trends. It reflects the massive scale needed for tomorrow’s connectivity and will likely incorporate early forms of AI-driven management. As AI continues to shake up the submarine cable ecosystem, we’ll see smarter networks that can predict and adapt to issues in real time, optimize themselves for efficiency, and handle the ever-growing tsunami of data (subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com). The next generation of subsea cables will be even more ambitious – perhaps globe-circling systems with self-healing capabilities and even higher capacities. Meta’s bold investment today signals that the era of private, AI-optimized global infrastructure is upon us, and it is setting the stage for how the digital world will be connected in the decades to come.

Final Thoughts

Meta’s Project Waterworth signifies a pivotal moment in the evolution of global connectivity. It marries unprecedented technical scale with a vision for a more connected (and Meta-served) world, all while navigating complex economic and political currents. In this investigative analysis, we examined how Waterworth’s high-capacity, AI-oriented design is pushing submarine cable technology forward, and how Meta’s strategic goals align with bridging connectivity gaps and reinforcing its own networks. We also compared this effort with similar big-tech cable projects, seeing a pattern of hyperscalers like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon taking charge of the internet’s physical underpinnings – a trend that has transformed content providers into the new telecom giants.

The implications are far-reaching: Waterworth and its ilk will enhance global internet capacity and reliability, potentially connecting underserved regions and fostering economic growth. At the same time, they concentrate infrastructural control in the hands of a few corporations, raising questions about governance, competition, and national security.

Project Waterworth will face significant challenges on its journey, from protecting against deep-sea hazards and cyber threats to satisfying regulators that span multiple continents. Yet, if Meta can successfully surmount these hurdles, Waterworth could become the blueprint for resilient, ultra high-speed networks in the AI age. It represents an emerging paradigm where AI and infrastructure reinforce each other: advanced networks enable AI everywhere, and AI in turn helps run those networks more efficiently.

Ultimately, the story of Project Waterworth is one chapter in the larger narrative of our connected future. It underscores that the internet is not ethereal – it relies on very tangible cables, investments, and engineering feats. As Meta and its peers race to wire the world with ever more capable undersea links, the result could be a planet where data flows more freely and intelligently than ever before. But it will require careful balancing of innovation with oversight to ensure this new infrastructure serves the global public interest as much as it serves corporate strategies. Waterworth’s progress in the coming years will be a telling indicator of how that balance is being struck, and its impact will likely ripple across the oceans and nations it links – ushering in the next generation of digital infrastructure.

Sources:

- Meta (Engineering at Meta) – “Unlocking global AI potential with next-generation subsea infrastructure” – Announcement of Project Waterworth (Feb 14, 2025)

(engineering.fb.com) (engineering.fb.com) (engineering.fb.com) (engineering.fb.com)

- SubTel Forum / Total Telecom – “One Cable to Rule Them All: Meta’s $10bn Plan to Build Global Subsea Cable” (Dec 2024) – initial report on Meta’s global cable plans

(subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com)

- SubTel Forum – “Meta Announces Project Waterworth” (Feb 2025)

(subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com) (engineering.fb.com)

- Engineering.fb.com – “2Africa Pearls subsea cable connects Africa, Europe, and Asia…” (Sept 2021) – Meta’s earlier cable investments and connectivity goals

(engineering.fb.com) (engineering.fb.com)

- Network Computing – “Amazon, Meta and Google Plan Subsea Cable Expansion” (Feb 2025) – overview of hyperscalers’ cable projects

(networkcomputing.com) (networkcomputing.com) (networkcomputing.com)

- TeleGeography Blog – “Content Providers’ Submarine Cable Holdings” (Dec 2024) – analysis of big four (Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon) dominance in cable capacity

(blog.telegeography.com) (blog.telegeography.com)

- Business Insider – “US-Hong Kong undersea cable project killed over national security” (Sep 2020) – example of regulatory blockage (PLCN)

(businessinsider.com)

- Capacity Media – “AI software monitors subsea cable threats as security concerns grow” (Feb 2025)

(capacitymedia.com) (capacitymedia.com)

- Ciena (SubTel Forum Magazine) – “The Impact of AI on Submarine Networks” by Brian Lavallée (2024) – insights on AI’s role in network infrastructure

(subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com)

- SubTel Forum – various industry news (Jan–Mar 2025) – e.g., approvals of new cables (Bifrost), technology upgrades (multicore fiber)

(subtelforum.com) (subtelforum.com)